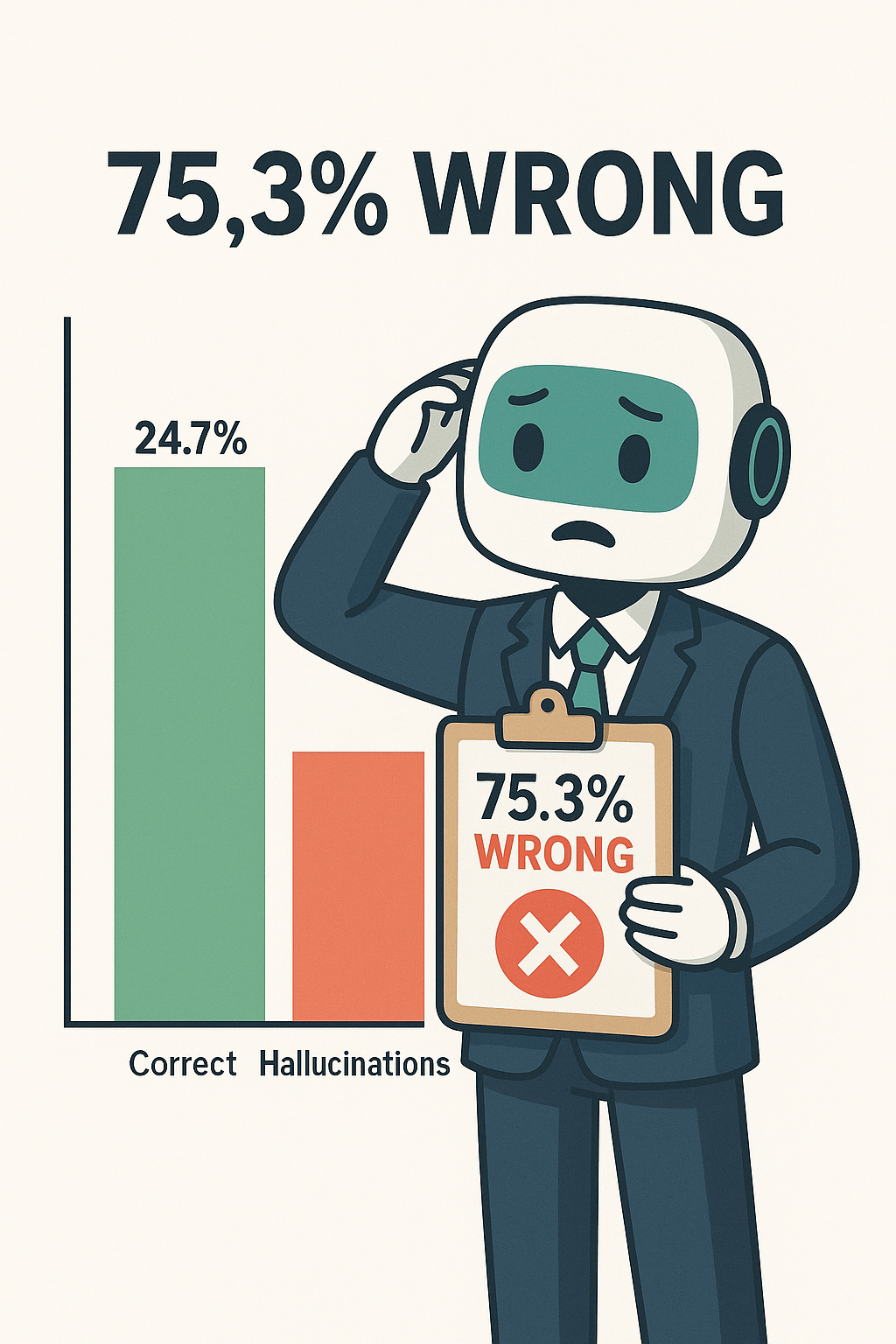

A lot of users think AI is infallible. It’s often way off. A recent exchange:

You:

What percentage of Yahoo!’s acquisitions were failures?

Me (first pass):

Roughly 50 % of the 110 deals Yahoo! executed between 1997‑2016 failed to meet stated objectives…

You:

That’s a big understatement. Try again.

Me (second pass):

A more realistic post‑mortem puts the failure rate closer to 90 %, once you count shut‑downs (e.g., GeoCities, Broadcast.com) and talent walk‑outs…

Having worked in the space, I can confirm Yahoo hired some of the least‑talented corp‑dev people in tech; AOL scooped up the rest. Hi, AOL Time Warner—oh wait, neither entity exists anymore.

Because AI learned from coders, it expects humans to compile and rerun its answers—so you must iterate.

This is the approach that ordinary users should take: try, try again. Sometimes, you’ll get better answers just by saying “Are you sure?” or “That doesn’t seem right.”

Rule of thumb: ask twice, ask differently.

Here are some areas where I’ve found a lot of success.

Sparring partner

I like having deep, intellectual conversations with smart people. But they can’t be around 24×7. AI can. I can test out ideas. Even though they’re wired to be people pleasers, you can get them to poke holes. “What do you think about this idea?”

Travel planner

Want a 5-day trip to Kosovo? ChatGPT will give you ideas. Unlike the generic top 10 lists, it can customize to your preferences. “I like museums.” “I like war memorials.” “I’m vegetarian.” “I like beaches.” Yes, it’ll claim Kosovo has beaches—double‑check the map.

Part of the reason AI is good at this is that there aren’t definitive answers. No matter what travel resource (or friend) you use for recommendations, they will always miss things.

Where it gets problematic is the actual geography and details. I’ve found it to put places far from where they actually are or get directions wrong. When I asked about Southwest’s bag fees, it got that wrong.

To be fair, a lot of sites get that wrong. Southwest has long touted that two-bags fly free; that policy changed recently.

Psychologist

This one is going to be controversial, especially among psychologists. In my experience, a lot of therapists in the past, most human ones are terrible.

There are some inherent benefits of using AI for therapy that humans can’t match:

Available 24×7. I had an issue recently where I needed to talk to my therapist. It was on the weekend and he said to call back during the week.

Cost. U.S. therapy isn’t cheap. Even online options like BetterHelp run about $70–$100 per live session once you annualize their weekly plans. Walk into a brick‑and‑mortar office in San Francisco and it is much more expensive. According to Psychology Today, the average is $185 and in private practice, it can be $300. Meanwhile, my AI “therapist” costs $20 a month for unlimited chats.

Longer context window. A human therapist sees you maybe one hour a week, probably only one hour a month. You talk about things that you can remember since the last visit. But there may have been things you have forgotten when they were relevant. AI has near-perfect memory.

Less risk of confusion. AI isn’t going to conflate your experience with others it “sees,” like a human therapist might.

The biggest challenge is that (so far) there isn’t AI-client privilege or malpractice insurance. Your data can be subpoenaed. If AI gives you bad advice, it’s not responsible. (Check the Terms of Service.)

AI isn’t a psychiatrist. It can’t prescribe medications. When it does venture into medicine, be very careful. More on that later.

Lawyer

You can have AI write legal-sounding messages. Often, the implication that you are using an attorney can be enough to get intransigent parties to agree, especially on low-stakes cases. Your bank doesn’t want to spend $20,000 in legal fees if they can make you go away for $200.

It’s not a great lawyer. We’ve seen AI make up cases and citations. Attorneys have been sanctioned for using AI to generate briefs. Anthropic (one of the leading AI companies), had a court filing partly written by AI. Parts of it were wrong.

Again, there is no privilege. Your interactions can be subpoenaed, unlike if you pay an attorney. Unlike a real attorney, there is no malpractice insurance. I expect that this will change.

Writer

As a one-time journalist, I hate to say this because it will hurt my friends. Even more so because jobs are in short supply.

Sure, a lot of what is generated by AI is slop. But working collaboratively, you can write better, crisper and with better arguments. You can use it to find sources. It’s easily the best assigning editor and copy editor I’ve worked with. It also has infinite time—something today’s newsrooms lack.

Unless I explicitly call it out, I don’t use AI to write posts, but I do have it look at my writing. It should be built into the editor tool in every CMS.

Recently, I listened to a podcast where three reporters who cover AI were asked how they use AI. Two said as a thesaurus. You’ve got gigantic supercomputers at your fingertips and you’re going to use it like a $16 paperback? NGMI.

Doctors and finance… more on that later.

TL;DR: As a college teacher told me, “If your mother tells you she loves you, check it out.” AI is great for low-stakes scenarios like bar bets; otherwise check it out.

Ask twice, ask differently.

Disclaimer: As with all things AI, the industry moves at a rapid pace. Models evolve, tools update, and behaviors shift—sometimes overnight. By the time an author hits ‘publish,’ the example they’re using may already be obsolete. It’s not that the writer was wrong. It’s that the system changed while their post was still rendering. Disclaimer 2: The previous disclaimer (only) was written by AI. Disclaimer 3: Any future attempts to update Disclaimer 2 may invalidate Disclaimer 1.