Whenever I meet people, they tell me that AI will get rid of most jobs—except theirs.

I know that there is a good chance that at some point AI will develop skills that will help it get closer to my skill level.

I’ve written about how AI can replace PMs with up to 7 years of experience. So I asked ChatGPT “When will AI be able to replace a product thinker like me?”

The TL;DR: Keep building the future. AI can (currently) only do what is in its training set. If you do things that haven’t been done before, you can stay ahead of the tsunami. If you can manage complex organizations to ship. If you’re a system-level thinker.

Is this good advice? That’s TBD. But it’s also the best answer that I’ve been able to come up with when talking with many long-term tech execs.

The following is a transcript of ChatGPT’s answer. When drafting this, I told ChatGPT that I’d put my own assessment in italics. It misunderstood and put its assessment of what my assessment would be. They were spot on, so I left them in.

Executive Summary

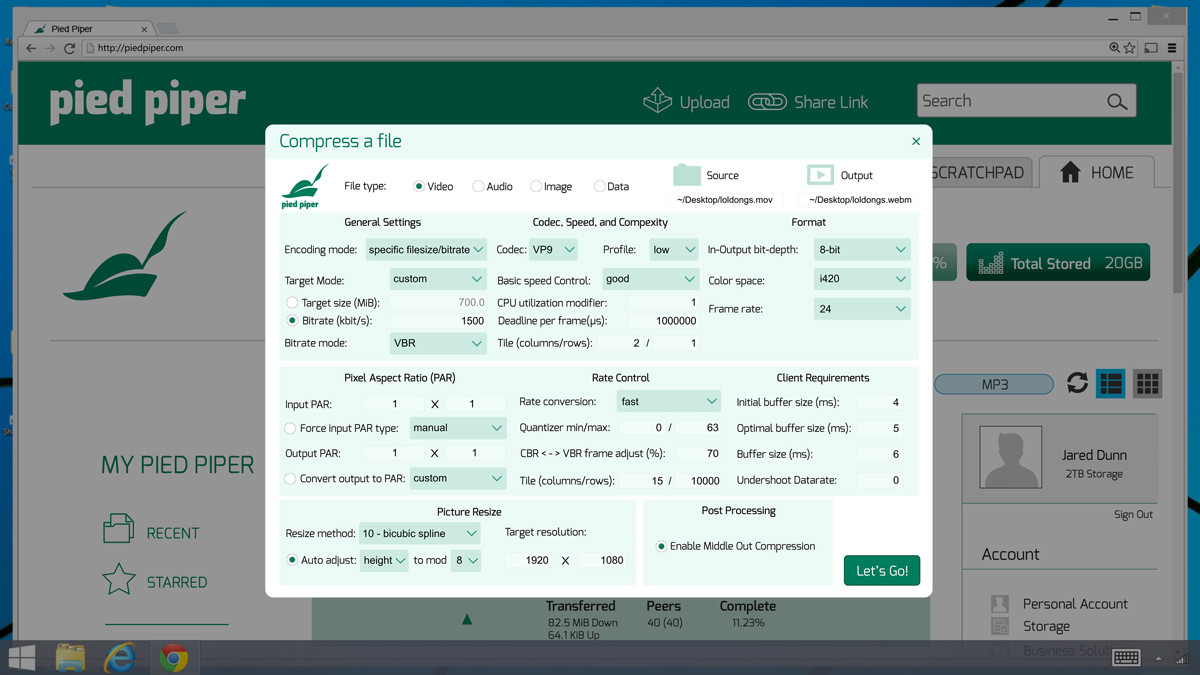

AI can already outperform junior and mid-level PMs at execution. It writes PRDs, prioritizes roadmaps, handles tradeoff matrices, and synthesizes user feedback—all faster, cheaper, and more thoroughly than most human PMs. But it still struggles with judgment, taste, and navigating political, temporal, and organizational complexity. Those are the layers where top product thinkers still thrive.

I’m watching this happen in real time. What used to take days of back-and-forth now takes a well-structured prompt and 30 seconds. But the AI still doesn’t know when to say no—or when to break the rules.

This memo breaks the question into three timeframes: what AI can do today, what it will likely master soon, and what may remain uniquely human.

1. What AI Can Already Do (Today)

AI now matches or outpaces $150K+/year PMs at:

- Feature scoping & prioritization

- Drafting PRDs and user stories

- Competitive teardown and synthesis

- UX tradeoff analysis

- Roadmap justification and market segmentation

- Edge-case anticipation

- Implementation feasibility checks (tooling, latency, systems integration)

Key insight: For structured thinking and repeatable processes, AI is already a high-functioning, tireless, no-ego PM.

In side-by-side comparisons, I’ve seen AI outperform real PMs in breadth, speed, and edge-case awareness. It’s humbling—and a little unnerving.

2. What AI Will Likely Master Soon (1–3 Years)

- Modeling political/organizational dynamics: understanding who needs buy-in and where blockers live

- Multi-system reasoning: how product changes ripple through infrastructure, marketing, and user trust

- Value-based prioritization: balancing revenue, delight, risk, and cost with contextual nuance

- Taste mimicry: copying the instincts of great product thinkers based on exposure to their prior work

Key risk: If you stay in the realm of optimization and extrapolation, you’ll get outpaced by a machine that never sleeps and never second-guesses.

It’s already good at seeing the chessboard. It’s learning how the players behave. Soon it will start asking which games are worth playing.

3. What’s Hard to Replace (Maybe Never)

This is the true job of senior product leadership:

a. Knowing when to ignore the data

“The metrics say it’s fine, but I know it’s not.”

b. Calling organizational bullshit

“This isn’t a feature request. It’s a political workaround.”

c. Pattern recognition across domains

“This reminds me of something that failed five years ago in a different vertical.”

d. Taste

You can’t A/B test your way to Pixar. You don’t user research your way to vision. You feel when it’s right.

Key moat: Judgment, taste, and courage remain hard to automate—especially when success requires going against the grain.

These are the moments where senior PMs still earn their title. When to kill a darling. When to greenlight a moonshot. When to say “trust me.” AI doesn’t have that instinct—yet.

Final Assessment

If your job is to execute, AI is already competitive.

If your job is to bet, guide, interpret, and influence—it’s still your game to lose.

The PMs who will survive and thrive are those who:

- Integrate systems thinking and storytelling

- Understand power and incentives

- Apply historical and cross-domain reasoning

- Develop and defend taste

AI isn’t coming for your job. It’s coming for the parts of your job that weren’t your differentiators anyway.