Today’s the 5-year anniversary of the launch of Google+. It was an unmitigated disaster for Google. Despite spending many man-years of development, endless hype in the media and Google’s attempt to cook the books on usage stats, the network is essentially dead.

Google+ failed for a simple reason: It blatantly tried to copy Facebook instead of playing to Google’s strengths.

We’ve seen a lot of attempts to copy successful products of others. Facebook tried to compete in search. Facebook tried to copy Flipboard (Paper), Instagram (Camera) and Snapchat (Poke). All of these attempts failed.

The only product in recent memory where the copy was more successful is Facebook Live, which is essentially Meerkat. I’d argue this was because Meerkat didn’t really solve a compelling user problem. Most people don’t need to broadcast 1-way video. Those that do need broad distribution, which Meerkat lost as soon as it was cut off from Twitter. (To the extent people want video, it’s 2-way, such as FaceTime, Skype or Hangouts.)

The reason these copies didn’t succeed? They didn’t incorporate what was unique about the new platform; what made them successful. In Google, that is search. In Facebook’s case, that’s social.

Google+ required you to replicate what you’d already done on Facebook. Create a profile, friend people and post. The unique and much better features of Google+ — Hangouts and Photos — were buried by comparison to the Facebook- product. Why would anyone repeat all the work they were doing on Facebook on Google+? Or switch to a platform where none of their friends are for no real benefit?

Google embedded Google+ everywhere it possibly could (YouTube comments, giant alerts, etc.) But it didn’t effectively do it where it mattered: in search. Hundreds of my friends use Google everyday. The results that they click on are more likely to matter to me than results that the general population click on. Despite the fact that I have a network of hundreds of people, I’m still searching in isolation.

If my buddy Bob spent 2 hours researching a trip to Senegal, shouldn’t I be able to learn from his efforts? Shouldn’t I be flagged that Bob did this work, maybe went to Senegal and had knowledge on the topic? Maybe I should reach out to him and learn about it? (Of course, this always needs appropriate privacy permissions. I shouldn’t be able to see Bob’s searches unless he makes them available to me.)

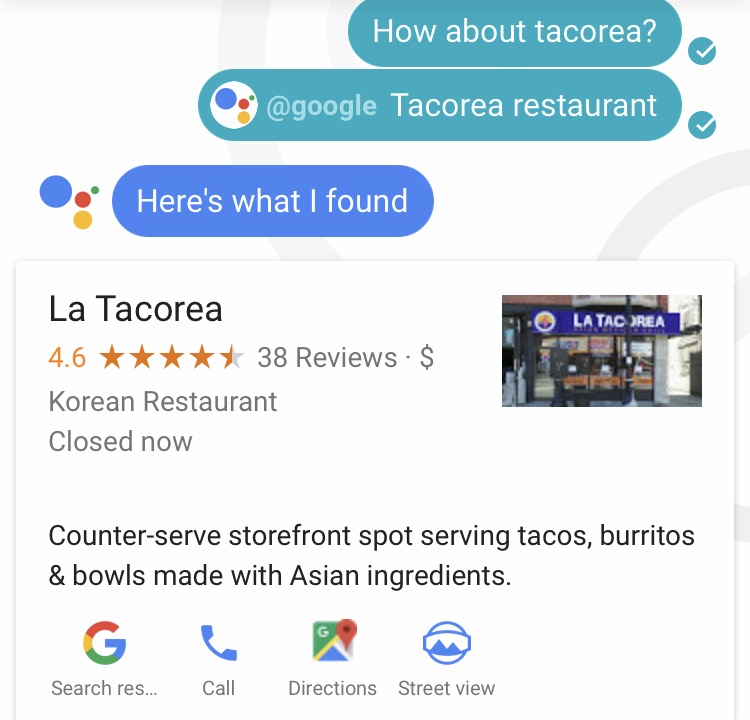

A friend wrote a review in Google’s local product of Rosewood Sand Hill. That should be front-and-center on this screen. It’s what I would consider by far the most relevant. But it’s nowhere to be found.

The right way for Google to play in social is to add a social layer to Google. If the value proposition to the consumer was “have your friends help you search,” instead of “use a version of Facebook without your friends,” I imagine Google+ would have been much more successful.

People search on Facebook. All the time.

Conversely, most of Facebook’s efforts on search, have focused on the search box. People search on Facebook all the time. But they don’t search in the search box, they search in status field.

If Facebook copies Google’s definition of search, they will (and have) failed.

What do I mean by people search on Facebook? Consider this example:

This is no different than a Google search for “Senegal”. Except, I am asking my friends, in a highly inefficient manner. There’s a high likelihood that someone in my friend network (of 600+ people) has been to Senegal or knows something about Senegal. But my post doesn’t efficiently reach those people. FB, through, NLP should identify this as a query for “Senegal” and present this post to my friends who have been to Senegal.

That creates a better search experience because I get expertise from people I actually trust.

If you expand distribution to friends of friends, you are almost guaranteed to find someone who has an answer. In this case, in an efficient way, my friend Mandy has expanded the search to her friend Chris in the last comment.

It could either be highly prioritized in news feed for them, or they could get a notification that says “Your friend Rakesh is looking for information about Senegal? Want to help him out?”

Modifying Facebook in this way also helps improve the social experience and increases the liquidity in the market. By expanding the distribution to my friends most likely to know the answer, I get an answer faster. This also opens up the possibility of creating new relationships or renewing old ones.

Scenario:

- I haven’t talked to friend Bill in a while.

- I post a “query” for Senegal.

- FB knows that Bill has been to Senegal. (Pictures posted from there, status updates from there, logins from there, etc.)

- FB surfaces the “query” to Bill.

- Bill sees it and responds.

- Bill and I reconnect.

Fact-based queries vs. taste-basted queries

This all works better for matters of taste vs. fact. Google is going to give you a much better, quicker answer for queries like the “value of pi” or “5+2” or “weather in Miami”.

Yes, I could ask this in Facebook — and I did:

More than an hour later, I still had no answer. (And my non-technical friends, who didn’t know what I was doing, would think I’m an idiot.) Mihir asked about chatbots — I’ll get to this in a minute.

But those are matter of facts — and, btw, have zero advertising against them.

Think about queries like “plumber,” “dentist,” “lawyer,” “auto insurance”. Those are queries of taste. And, it may shock people, but that’s where you make your money in search! Travel, law, professional services and insurance are among Google’s top money makers.

While many people, including Wall Street analysts, treat search as a monolith, search is actually a collection of verticals. Each has different levels of monetization. Many fact-based queries have no advertising against them.

Facebook doesn’t have to solve the queries of fact. Leave those to Google. (It could, but people aren’t searching FB for those.)

Facebook can pick off the higher-value queries and the ones that are most likely to add to the FB experience and value proposition: a place where you come to interact with your friends.

FB can also use these “queries” as a way to turn its ad into higher revenue, intent-based ads. In addition to your friends comments, you’d see — clearly identified — responses from advertisers to your query.

Someone who posts a query “anyone know of a good hotel in London?” could be presented with an advertiser comment for “hotels in London.” This presents a highly relevant ad that someone could turn to immediately. (It could also be time delayed — if I don’t get a response from a friend, the advertiser comment shows up.)

Bots

Facebook is trying to do this in a ham-fisted — and annoying and needlessly interruptive way.

I was recently hit by an Uber while walking across the street. My cousin asked me about it on Messenger. Here’s what happened:

My cousin is asking how I’m doing after I was hit by an Uber. Messenger is throwing an ad for Uber in both of our faces. (Not only once, but three times. See my post on bots.) There are some great uses for bots. Sticking irrelevant ads in front of people isn’t one. (I’ll talk about good use cases in a future post.)

Often, you’re forced into a space by business needs or the stock market demanding that you have a “search” or “social” strategy. Or there’s a hole in you business model. See also: wireless carriers in payments, video, content, pictures.

The easiest thing to do is to try to copy someone else who has been successful. But if they’re already dominant, how are you going to win? You can’t just create something to plug a hole in your business strategy; you need to plug a hole in the customer’s needs.

These are just two big examples of how you could win by playing to your own strengths — and your user’s frame of reference about your product.

When designing new products, you should figure out what makes you different and better. Then build off that.

A Tesla enthusiast

A Tesla enthusiast